Nestled in the breathtakingly beautiful and serene heartland of northern Thailand’s Nan province lies the indigenous communities of Nam Chang Patana and Nam Ree Patana. These villages are located close to Thai-Laos land border in the midst of a dense, lush forest surrounded by majestic mountains.

However, these idyllic villages and surroundings are threatened by the presence of the Hongsa power plant and coal mine, situated some 20 kilometers away across Thailand’s border. The power plant, fuelled by locally extracted lignite coal, has been a source of constant significant concern for the indigenous Lua communities. Concerns range from environmental degradation to human and wildlife health hazards, with communities struggling to find viable solutions.

Through candid interviews with community members, we gained insight into their experiences and concerns about the impact of the power plant on their villages and communities.

Jeab observes the impact on farming

Jeab, a 30-year-old villager from Nam Chang Patana, is one of the more vocal and outspoken community members against the coal-fired power plant. The indigenous Lua people, to which Jeab belongs, have been living in their village since time immemorial. Farming is the Lua people’s predominant livelihood, with rice, corn, and coffee as the main crops.

The power plant, operational since 2016, produces a combined 1,878 megawatts of electricity, making it the largest of its kind in Laos. Initially unaware of the plant, Jeab, who grows and sells coffee, has been observing her environment for several years, revealing a significant change in their farms and livelihood.

Our livelihood depends on farming. At first, I did not see anything wrong. But, observing for years, the villagers started talking about changes in their crops, trees, and farms. There was a huge reduction in quality harvests. If our products are damaged, we can’t sell them. We can’t earn money. We can’t even eat them.

Jaeb, a villager from Nam Chang Patana

While the power plant is only twenty kilometers across Thailand’s border, Jeab heard about it just six years ago when a group of university researchers started coming to the village to collect soil samples for laboratory testing.

“Observing the power plant from this spot, I see smoke coming out for long hours. So I wonder if the smoke, which comes from Laos, impacts us on the other side. I think there is something in that smoke that pollutes our farms,” added Jaeb.

Namwhan warns about the impact on human health

In Nan’s village, fish caught from rivers and creeks are a vital source of protein. But since the Hongsa power plant became operational, the indigenous Lua community in Nam Ree Patana, some ten kilometers south of Jaeb’s village, has become more concerned about the plant’s impact on the aquatic ecosystem and human health.

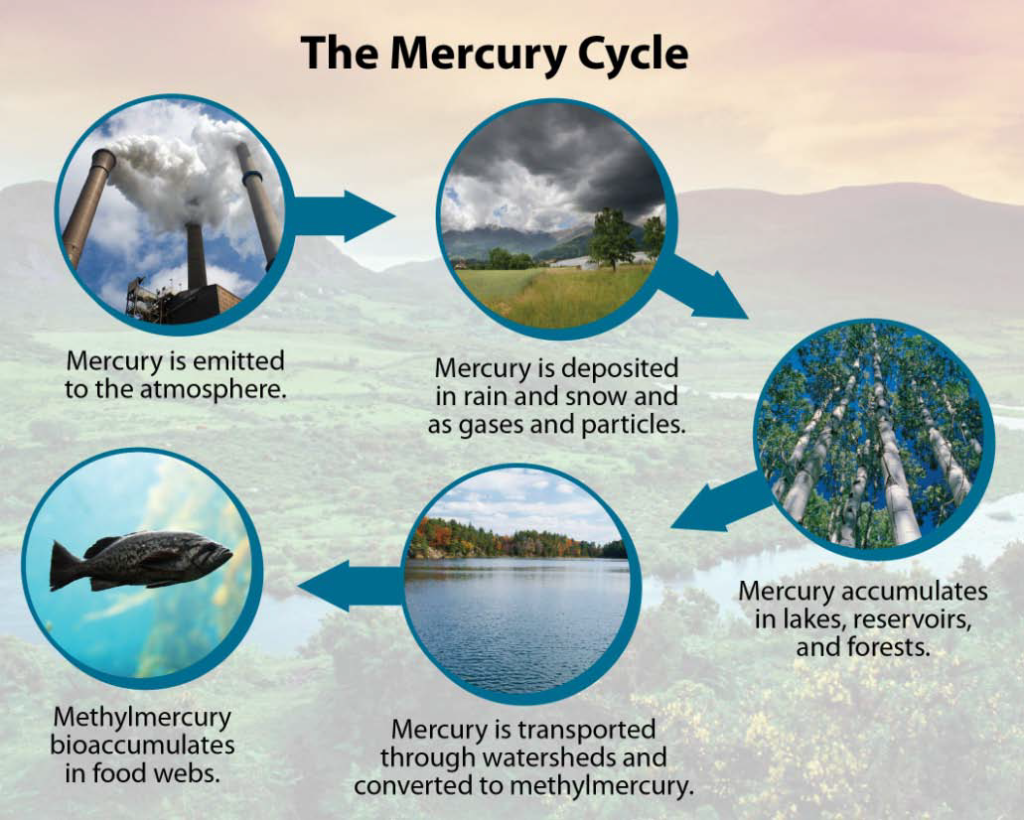

The burning of lignite coal is a significant source of mercury, a toxic pollutant to human health, wildlife, and the environment. It can travel long distances when released to the atmosphere, before being deposited back on the earth’s surface on land and water. Once mercury enters the aquatic ecosystem, it is easily absorbed by fish, which poses further health risk to humans if consumed.

“We used to eat the fish that we caught in the creeks in the past. It all changed, however, after laboratory results from the hair samples collected from the local villagers showed a significant level of mercury. Since then, we tried to avoid eating fish from the creek,” said Namwhan, who is currently helping university researchers gather data samples in her village.

Aside from mercury, other typical pollutants produced by power plants, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, can cause respiratory diseases. Namwhan, who also serves as a leader for the community’s health group, saw an increased number of respiratory-related cases in her village since the power plant became operational.

I talked to the doctors and nurses in the local hospital. They observed the increasing number of patients with respiratory diseases.

Namwhan, a villager from Nam Ree Patana

Prathan Thiep calls for a collective effort to address the issue

According to the website of Hongsa Power Company, which operates the coal-fired power plant, the facility uses advanced technology and environmentally-friendly machinery to generate electricity. The company also stated that the plant’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) was approved, and research has been conducted on the plant;s electricity generation and any waste it produces from the process. Consequently, the company installed monitoring systems in the surrounding Laos villages in Hongsa and Ngern to check the levels of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the air.

“Several villagers had the chance to visit the power plant in Laos. Overall, they said the power plant has many equipment installed to filter the pollutants. But I don’t believe that. I think the company prepared well to present the power plant positively,” said Prathan Thiep, deputy head of Khun Nan, the tambon (subdistrict) where the villages of Nam Chan Patana and Nam Ree Patana are located.

During the construction of the power plant in Laos, the EIA only involved the residents directly around the site, and failed to consult the indigenous Lua communities on the Thailand side of the border. Moreover, there is no consistent system in place to monitor the air quality in Nam Chang Patana and Nam Ree Patana, which are located near the power plant.

In 2023, several communities in Nan province filed a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT) against the company for its failure to address transboundary pollution caused by the power plant.

We fought, but it is not the best yet. All of us have to walk hand in hand to solve the problem and come up with a plan to address the issue.

Prathan Thiep, deputy head of Khun Nan

The Hongsa coal-fired power plant has a contract to generate electricity until 2040. Although it is located in Laos, the power plant is partly owned by Thai companies and financed by Thai banks.

The NHRCT, an independent Thai government agency responsible for receiving and addressing complaints related to human rights abuses, is currently conducting an inquiry into the transboundary impact of the Hongsa power plant. As part of its mandate, the commission is authorized to recommend remedial measures for communities affected by Thai transboundary investments.

Interested to learn more? The regional media outlet Channel News Asia published the story “Mercury Rising: Power and Poison in Northern Thailand,” which is available on its website and YouTube.