Thailand’s National Energy Reform Committee has just announced a plan to reform the country’s energy production and consumption by promoting renewable energy and good governance in the energy sector.

But it’s clear that the country still has a long way to go to improve its energy planning. Last month in Bangkok, an energy policy training organized by International Rivers, the Mekong Energy and Environment Network (MEENet), Palang Thai, and EarthRights International (ERI), showed that the first steps should include pushing energy efficiency, advancing renewable energy through the Alternative Power Development Plan and cutting foreign imports.

Thailand’s Power Development Plan (PDP, 2015-2036) sets out energy supply targets and strategies whereby the main sources of energy are natural gas supplies and foreign imports. The PDP’s heavy focus on foreign imports has led to growing Thai investments in dams and coal in other countries. These investments have caused a wide range of environment and social impacts, including human rights violations and damage to local livelihoods.

There is a growing chorus of critics calling to reform the PDP, reduce Thailand’s reliance on natural gas and cut foreign imports. These steps, combined with a move away from damaging mines, dams and coal projects, could position Thailand as a leading renewable energy “Tiger” in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

A Narrative of Fast Economic Growth and Overblown Demand

According to Bloomberg, Thailand’s economy saw remarkable growth in 2017 with the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 increasing 3.7%, though this growth may not continue this year and is expected to slow down in 2019. But the Power Development Plan was drafted to match economic growth like Thailand saw in 2017. It’s designed to supply energy to meet the rapidly growing economy. But are these economic and energy forecasts overblown?

The current Power Development Plan emphasizes energy security, boosting the economy and cutting environmental impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions. The country’s power production capacity as of April 2017 stood at 44,579MW, including significant imports from hydropower dams and coal-fired power plants in Laos as well as some small-scale renewable energy suppliers. According to the Plan, Thailand needs to install an additional 24,736 MW of capacity by 2036. The Plan states that this would provide a 15% reserve margin.

But according the energy analysis conducted by the Development Bank of Singapore in July 2017, projects outlined in the Plan actually will provide a 34% reserve margin, based on Thailand’s recent peak demand of 29, 619 MW in May 2016. If energy conservation plans are implemented, the Plan could provide a reserve margin as high as 48%.

Communities along the Salween River in Karen State, Myanmar protest against hydropower projects with signs reading “The Salween River is Not for Sale.” Almost all of the power from proposed dams on the Salween, such as Hatgyi and Mongton, would be exported to Thailand. Photo: John Bright, Chulalongkorn University.

Too Big, Too Dirty: Overblown Demand Used to Justify Coal Power and Big Hydropower

Nevertheless, the Plan is used to justify aggressive plans to develop coal domestically and hydropower dams in neighboring countries, especially Laos and Myanmar. Domestically, the controversial coal-fired power plant in Krabi province dominated the energy agenda over the last year. While the main argument for building the Krabi plant is to meet PDP targets, and to prevent frequent power blackouts in the South of Thailand, the communities affected by this project and CSOs argue that there are massive flaws in the Environmental Health Impact Assessment Report. The Report has been based on inadequate studies that downplay the importance of income from tourism, which Krabi may lose if the plant is built. There has also been a clear lack of meaningful public participation in decision-making around the project.

But the Power Development Plan also shows Thailand will continue to rely on damaging energy projects abroad, based on deals outlined in Power Purchase Agreements with neighboring countries. Electricity from the already-operational Nam Theun 2, Theun Hinboun, Huay Ho, Nam Ngum, and Nam Ngieb dams, as well as the Hongsa coal project in Laos will continue to be exported to Thailand. The Hongsa coal-fired power plant project is being developed by two Thai companies: Banpu Power and Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holding, two of the largest coal developers in the region. Thailand and Laos signed an MoU in 2007 and the project first began operation in June 2015. Power purchase deals brokered at the ASEAN Summit in 2016 and additional agreements between Laos and Thailand brought the total installed capacity of electricity imported to Thailand from Laos to 9000 MW.

But further projects to import electricity are still proposed. EGAT is developing transboundary transmission lines between Malaysia and Thailand, as a “plan B” to import electricity from Malaysia if popular resistance succeeds in stopping the Krabi plant. The PDP states that Thailand will purchase approximately 7000 MW from the proposed Mongton Dam on the Salween River in Myanmar, financed by EGAT International, and approximately 1000 MW from the Xayaburi Dam, financed by Ch Karnchang, a leading Thai investor in construction and engineering. Since these plans were announced, the public has raised concerns over environmental and social impacts of the dams. The Mongton dam will flood an area the size of Singapore. The Xayaburi dam will significantly change the nature of fish migration in the Mekong, cutting off fish and food supplies for communities throughout the river basin. They will face the collapse of their livelihoods and chronic food insecurity. These externalities have not been adequately considered in the cost of Thai investments abroad.

Impacts from dam and coal projects are felt most by the poor, especially those who rely mostly on land and river-based livelihoods. Their rivers, oceans and coastal resources are polluted due to the very coal projects which are built to serve Thailand’s overblown economic needs and EGAT’s interest.

EGAT Does It All: A Profit-Driven PDP and an Overstated Energy Forecast

The PDP was approved in May 2015 by the then-recently-formed National Council of Peace and Order (NCPO) military government. Since then, critics from civil society have raised concerns that EGAT overestimates its forecasted energy needs. Civil society and energy experts alike are worried that these estimates and excessive reserve margins are used to justify a PDP that pushes damaging projects and ignores greener renewable energy options.

Specifically, the projection that the reserve margin would increase to 39% has been publicly criticized as irrational, when compared to the global standard of 15%. As Thailand’s natural gas production capacity has reached its peak, the PDP has increased the reserve margin to account for risk factors such as gas pipeline shutdowns, power trade deals falling through, and bilateral projects being delayed. As a result, the PDP pushes many projects that are merely “plan B,” including unnecessary coal fire power plants and dams, domestically and abroad.

Critics have labeled EGAT’s energy forecast as for-profit business as usual: it is necessary for EGAT to maintain high levels of investment in energy in order to maintain its legitimacy and fuel EGAT’s profitable monopoly in Thailand’s energy sector. Critics further said the PDP drafting process lacks public participation and public scrutiny. It is mainly driven by EGAT, pushing for profits instead of effective energy diversification and responsible energy governance. This makes it all the more essential to follow the recent energy reform plan’s emphasis on good governance in the energy sector.

Reading Between the Power Lines: Thailand’s Position as ASEAN’s Electricity-transmission Hub

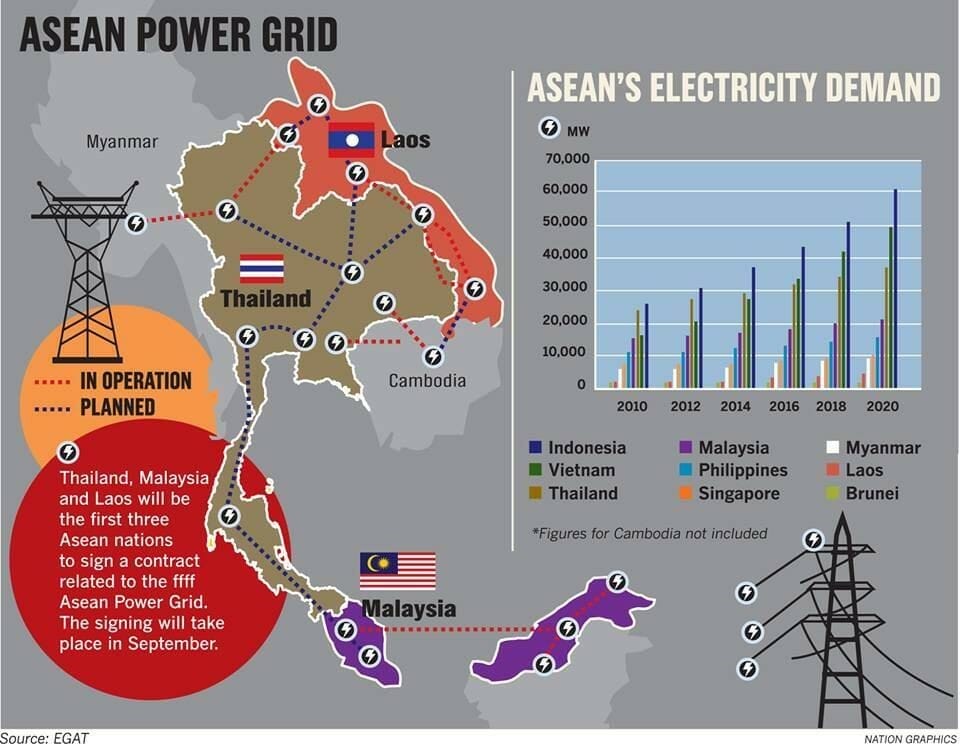

But Thailand’s energy import plans are embedded in a regional development agreement. In September 2017, the Prime Ministers of Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia met at the ASEAN Ministers of Energy Meeting and signed a historic electricity trading agreement to bring electricity from Laos to Malaysia via Thailand. The agreement represents the first step to turn the ASEAN Power Grid into a reality.

The ASEAN Power Grid is a flagship program first mandated in 1997 by the ASEAN heads of state and governments under the vision to enhance energy connectivity, market integration and achieve energy security for all. While Laos will get paid from selling electricity, Thailand will get paid for the use of its transmission lines and Malaysia will get the electricity. Because Malaysia seeks to reduce reliance on fossil fuels but still views hydropower as sustainable, this plan will emphasize Laos’ position as the “battery of Asia” and promote the development of dams. With this vision, Thailand becomes the ASEAN electricity-transmission hub and EGAT is given a mandate to strengthen the electricity grid capacity and connect ASEAN countries via its own grid system. This mandate will be used as extra justification beyond the PDP for unnecessary, dirty and damaging energy projects.

Improve not Import: Improve Energy Efficiency, Cut Damaging Projects and Develop Renewables

But the PDP isn’t the only option. The latest Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP 2015) for Thailand outlines how the country could do more to promote renewable energy. It sets out a plan to install high-efficiency technology and invest in solar and wind power. The AEDP 2015 sets out a plan to reach 30% renewable energy generation capacity by 2036, and a recent study suggests that an even higher percentage is within reach. Following the AEDP 2015 would allow Thailand to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels and eliminate eight billion dollars of health and environmental impacts per year.

Thailand’s 20-year Energy Efficiency Development Plan (2011-2030) sets out the target to cut energy consumption by 20% by 2030, compared to what energy consumption would be by then if current trends continue. In line with this target for alternative energy, EGAT should consider very thoroughly how these energy conservation measures should be promoted. Measures such as cutting consumption, managing peak loads, and appropriate demand side management are crucial, as are steps to improve efficiency by Thai consumers including industries. But all of these efforts could be undermined unless the PDP’s overblown estimates are reconsidered.

Thailand’s plan to reform energy production and consumption, released two weeks ago, is another sign that the current PDP is problematic. By focusing on renewable energy and reducing imports from dirty sources abroad, Thailand could position itself to be a leader in green energy: a “tiger” in the ASEAN energy landscape.

Local fishers in Krabi, Thailand gather around a giant banner with a message “Protect Krabi” as they take part in a demonstration against a local coal-fired power plant project near a mangrove forest in Krabi’s river estuary on November 9, 2014. Photo: ©Greenpeace.

Note: Thailand’s Extra-Territorial Obligations Watch Working Group (Thai ETO-Watch) is a coalition of Thai CSOs and NGOs working to stop human rights violations, environmental damages, and social impacts caused by Thailand’s outbound investments. EarthRights International is a member. We monitor practices of Thai investors in the Mekong countries and Myanmar, and support communities who are negatively affected by these projects in defending their rights to natural resources and remedies in cases of abuses. We advocate for policy changes to enforce the extraterritorial obligations of Thai investors, including to conduct due diligence. We work with communities affected by Thai investment abroad, academics, CSO, government and the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT) to develop mechanisms to hold Thai investors accountable.