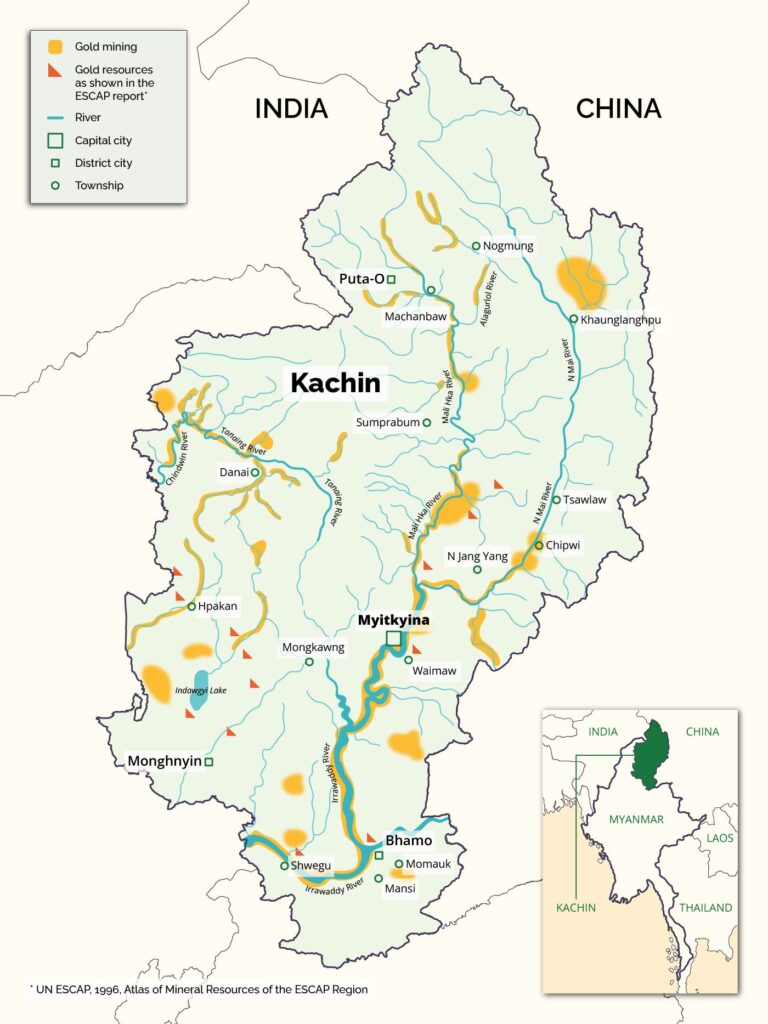

Kachin State is situated in the northernmost part of Myanmar and shares borders with two large countries: India to the west and China to the north and east. The state is a remote and rugged land characterized by densely forested hills, valleys, and wild rivers. As it is located near the base of the Himalayan Mountain range, it is one of the rare places in Southeast Asia where snow-covered peaks can be seen and visited.

Sadly, the once-pristine landscape is now facing an urgent environmental crisis. Numerous reports have highlighted that its forests bear the scars of an increasing number of excavated pits, and its rivers are marred with floating dredges due to gold mining—a stark contrast to its former natural splendor.

To witness the escalating environmental degradation, I embarked on a journey to Kachin State. After taking several flights from Yangon to Mandalay, then to Myitkyina, and finally to Puta-O, I arrived at my destination. The night was cold, but being in a different place heightened my sense of adventure and excitement.

In the following days, I traveled to several locations around the town, meeting with the locals and listening to their stories about how gold mining has disrupted their lives and livelihoods.

Landscape changes in Alan Khar

On this trip, I visited the village of Alan Khar, located 30 miles to the east of Puta-O. The journey took two hours, winding through forests, rivers, and rice paddies. The locals of Alan Khar, like many in Kachin State, have a deep connection to their lands. Their livelihoods rely on farming, hunting, and gathering forest products. Meanwhile, some of them engage in the traditional method of gold collection using hand tools like shovels and pans, a skill that has been passed down through generations.

However, the traditional life of the locals in Alan Khar is being threatened. The previously tranquil Mali Kha River near the village is now filled with floating dredges, which use mechanized equipment to extract gold from scooped sediments in the riverbed. This mechanized mining activity not only disrupts the natural flow of the river but also threatens the livelihoods of the local people who rely on the water source.

At what price?

Alan Khar is just one of the many villages affected by the gold rush in Kachin State. Recent information and figures on gold mining in the state are difficult to access due to the country’s limited data on its extractive industry. In 2004, however, a civil society organization produced a report highlighting the presence of gold mining in major rivers and on land where gold-yielding sediments are found. It further claimed that since the 1990s, the artisanal and small-scale gold mining that was commonly practiced among the locals has gradually been replaced by mining using heavy machinery, which is more destructive to the environment.

Myanmar is profiting enormously from gold mining. According to a 2018 document from a community group monitoring mining, the country’s gold production is estimated at 54,400 troy ounces (1,692 kilograms) per year, valued at $76 million at that time.

The ongoing armed conflict in Myanmar has led to increased exploitation of natural resources by local and foreign miners. Since the military junta seized the government in a coup d’etat in 2021, there has been a tenfold increase in illegal gold mining in Kachin State. Moreover, the little progress made on environmental management reforms by the previous civilian government has suffered a significant setback. In the 2022 Environmental Performance Index, Myanmar ranked 179th out of 180 countries on climate change performance, environmental health, and ecosystem vitality.

Myanmar’s lack of regulation and weak enforcement of the law allows extensive and uncontrolled gold mining to continue, benefiting only a few individuals and companies. Meanwhile, most local communities do not benefit from the industry. Instead, these communities suffer from environmental degradation, depriving them of access to clean water, lands, and other natural resources that formerly provided their livelihoods. Moreover, communities are not compensated for their losses, leading to a severe violation of their rights.

Environmental damages

Gold in Kachin State is mainly discovered in tiny fragments from river sediments. Extracting this valuable metal requires the environmentally disruptive method of digging soil and rocks from the riverbed and then processing them through several machines. The miners repeat this process many times until they can no longer gather gold dust.

The miners typically remain at a single site for about three months but never for more than a year. Once gold is depleted, they move to a new location, leaving behind a devastated landscape that not only lacks gold but also bears witness to the irreversible and long-term environmental harm caused by gold mining.

The Mali Kha River near Alan Khar has undergone significant changes due to gold mining activities, leading to the formation of mounds of discarded soil and rocks. These mounds disrupt the river’s natural flow, which can negatively affect aquatic habitats and species that depend on the river’s water flow for mating and egg-laying.

In addition, gold mining contributes to riverbank erosion and the deforestation of nearby areas by cutting down trees and vegetation to clear the land and build mining camps and temporary roads for transporting equipment.

Mercury contamination

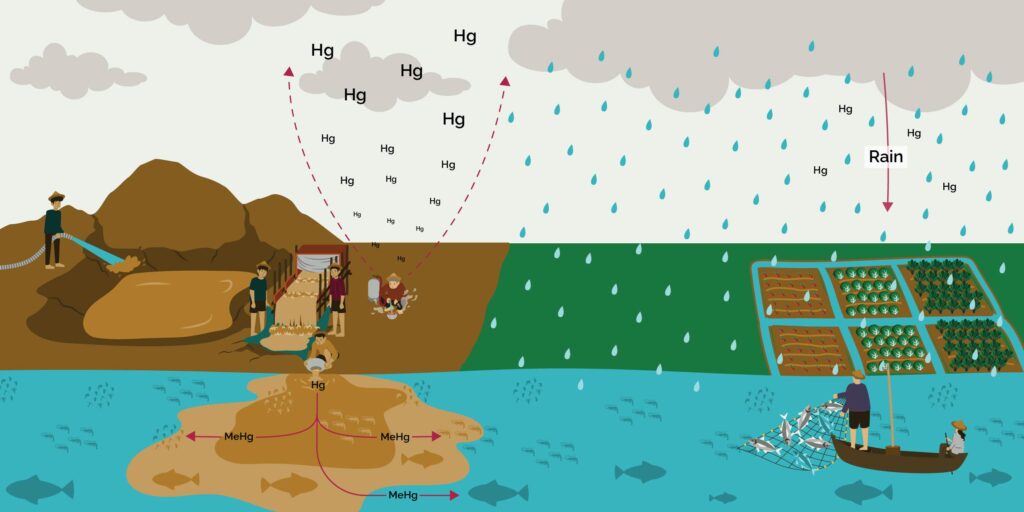

Mercury, a highly toxic chemical, has been extensively used in gold mining in Myanmar despite the health and environmental risks it poses. Miners mix the chemical barehanded with gold dust to create an amalgam, which is heated up at a later stage to evaporate the mercury and obtain solid gold.

The waters near mining sites are contaminated with mercury that has been carelessly disposed of by gold miners. Once the chemical enters the river’s water system, it is transformed into methylmercury. Methylmercury is a toxin that can get into the food web as it is easily absorbed by small aquatic animals, which large animals and humans then consume. This process of bioaccumulation, where the concentration of a toxin increases as it moves up the food web, poses a significant health risk to the local communities who rely on the river for their food and water.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified mercury among the ten chemicals of public health concern due to its potential to cause several health problems that can arise from handling or being exposed to it. Handling mercury with bare hands causes skin irritation. Inhaling the vapor produced by heating a mercury-laden amalgam, which gold miners do to obtain solid gold, can lead to neurological and behavioral disorders. The symptoms include cognitive and motor dysfunctions, insomnia, memory loss, neuromuscular effects, and tremors. WHO advises pregnant women against consuming fish and other aquatic animals contaminated with methylmercury, as it can harm the development of their babies in the womb. Babies exposed to the toxin may have problems with cognitive thinking, memory, attention, language, and fine motor and visual-spatial skills.

Land grabbing and corruption

With increased competition among gold miners and with many sections of the river heavily mined, gold miners are now excavating pits further inland, closer to the villages. Some even encroach into farmlands and excavate without consent from the landowners.

The situation has created a vicious cycle in which villagers, unable to monitor their lands, sell them at low prices out of fear of eventually losing them to gold mining. Furthermore, the rampant illegal selling of land by village officials is forcing people out of their lands.

“In one of the communities, the village chief has made money by selling land to gold miners. He used to be against mining in the past,” narrated Khin Zaw.

Gold mining not only contributes to land grabbing but also fosters corruption. Many gold miners in Kachin State operate without a license, making their activities illegal. Miners rely on informal agreements often involving the payment of bribes, averaging 20 lakh kyat (950 USD) per month, to Myanmar’s military, pro-junta militias, or ethnic armed groups—whoever controls the area where the gold mine is. Additionally, gold miners employ other tactics to gain the trust of the local community.

“Sometimes, gold miners influence village leaders by taking them to nice hotels in town. They may also donate an ambulance or build a small monastery, a dormitory for teachers, or a football field. That is how gold miners keep the locals silent and prevent complaints from them,” explained Thein Han.

Resisting gold mining

Despite feeling unsupported by the government institutions and the armed actors who control their territory and fearing social backlash for speaking out, some villagers are vocal about their resistance to gold mining.

“If we give up and let them do what they want, there will be no land for our livelihood. These lands belong to our community. As you can see, we do not have much farmland in our village area,” said Hla Shwe, a 60-year-old indigenous villager.

The ongoing gold mining problem in Kachin State serves as a clear reminder of the devastating environmental and social consequences of unchecked mining. The state’s pristine landscapes, once characterized by lush forests and natural-flowing rivers, are now marred by extensive gold mining activities. This degradation of the landscape not only poses an environmental problem but also significantly disrupts the lives of the local communities, whose traditions, livelihoods, and health are intricately linked to their land and the river.

While the pursuit of gold may bring economic benefits to a small group of people and mining companies, gold mining comes with immense long-term costs to the environment and the local population. The destruction of river ecosystems, deforestation, and toxic contamination pose significant risks to food security and public health. Additionally, the land grabbing and corruption associated with gold mining activities further heightens the challenges faced by the local communities in Kachin State.

Htet, an EarthRights School alumnus from Myanmar, submitted this blog.

Notes:

- The main photo used on this blog was sourced from Wikimedia Commons, taken by Anton Gutmann.

- The names of people interviewed in this blog were changed to protect their identities.

- The map included in this blog was adapted from the 2004 report “At What Price? Gold Mining in Kachin State, Burma,” published by Images Asia Environment Desk. It is stylized and not to scale. It does not reflect on the legal status of any country or area or the delimitation of any frontiers.

- This blog was submitted for inclusion on the EarthRights website. It represents the author’s opinion based on interviews with communities and does not represent the position of EarthRights or its staff. The author bears responsibility for the accuracy of the content in this blog.