Tomorrow, the world celebrates World Day of Indigenous Peoples on the tenth anniversary of the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Declaration addresses cultural rights and identity, as well as rights to education, health, employment, and language. It outlaws discrimination against indigenous peoples and promotes their complete participation in matters that affect them. It also ensures their right pursue their own priorities in economic, social, and cultural development, and encourages strong and cooperative relationships between governments and indigenous peoples.

The reality of indigenous people’s experience, however, does often not align with the goals set out a decade ago. Indigenous peoples are so often caught in the crosshairs of the world’s most powerful corporations and most valuable resources. Governments, instead of encouraging cooperative relationships and providing opportunities for indigenous communities to make their own decisions, often do the opposite in the name of profit and “economic development.”

It’s important that we understand the challenges, acknowledge the setbacks, and celebrate the victories of indigenous communities around the world in their global struggle against corporate power. We are fortunate enough to work alongside some truly inspiring indigenous communities around the world. Here are just a few stories of resistance and resilience.

“…We can’t eat money if we don’t have water for humanity’s survival.”

The U’wa Nation of Colombia holds a deep spiritual connection to the environment but corporations and uncooperative government officials are threatening that relationship with oil extraction and tourism. The U’wa have endured years of corporate overreach – but they’ve also proven themselves resilient and determined, like defeating Occidental Petroleum 15 years ago. Recently, the U’wa mobilized to protect their sacred Zizuma, a snow-capped mountain located in Colombia’s Cocuy National Park. The country’s National Park Service wants to open the park to tourists but the U’wa is concerned about the possible impacts tourism will have on their land.

Last year, we attended the Summit in the Defense of Life, Territory, and Natural Resources in Colombia. The summit brought together both Colombian and international lawyers, activists, and filmmakers together for the first time. It was a powerful showing of solidarity and reaffirmed why it is that we do this work – working closely with communities and earth rights defenders to protect their environment and hold corporations accountable.

“We call this a summit, because it is as if we are climbing a mountain together.” — Edwin Tegria, community leader, U’wa Nation (Colombia)

“We started a lawsuit so that we could win.”

For 30 years, Adolfina García and her family suffered the consequences of contamination caused by the oil companies operating in the Corrientes region of northern Peru.

“As soon as the company entered, there were oil spills. They spilled crude oil – there were plants that wouldn’t grow.” – Adolfina García

It wasn’t long before children in the villages began to get sick, including Adolfina’s son, Olivio Salas, who died when he was only 11-years-old. Adolfina believes his death was due to oil contamination caused by the negligent oil companies operating in the area.

In 2007, we filed a lawsuit on behalf of Achuar communities against Occidental Petroleum (Oxy) in Los Angeles, where the company is based. After a six-year battle, both parties settled in March 2015. Oxy agreed to provide assistance to five Achuar communities to carry out a variety of community development projects.

To learn more about the Achuar’s journey to justice, watch Oil in the Corrientes.

“Lord, take my soul. But the struggle continues.”

The Niger Delta is a hotbed for oil companies and they have left a path of destruction ever since they arrived in the region in the 1950s. In the early 1990s, Shell requested military support to build a pipeline through Ogoni. It wasn’t long before individuals living in Ogoni were murdered by the Nigerian military, who were compensated by Shell.

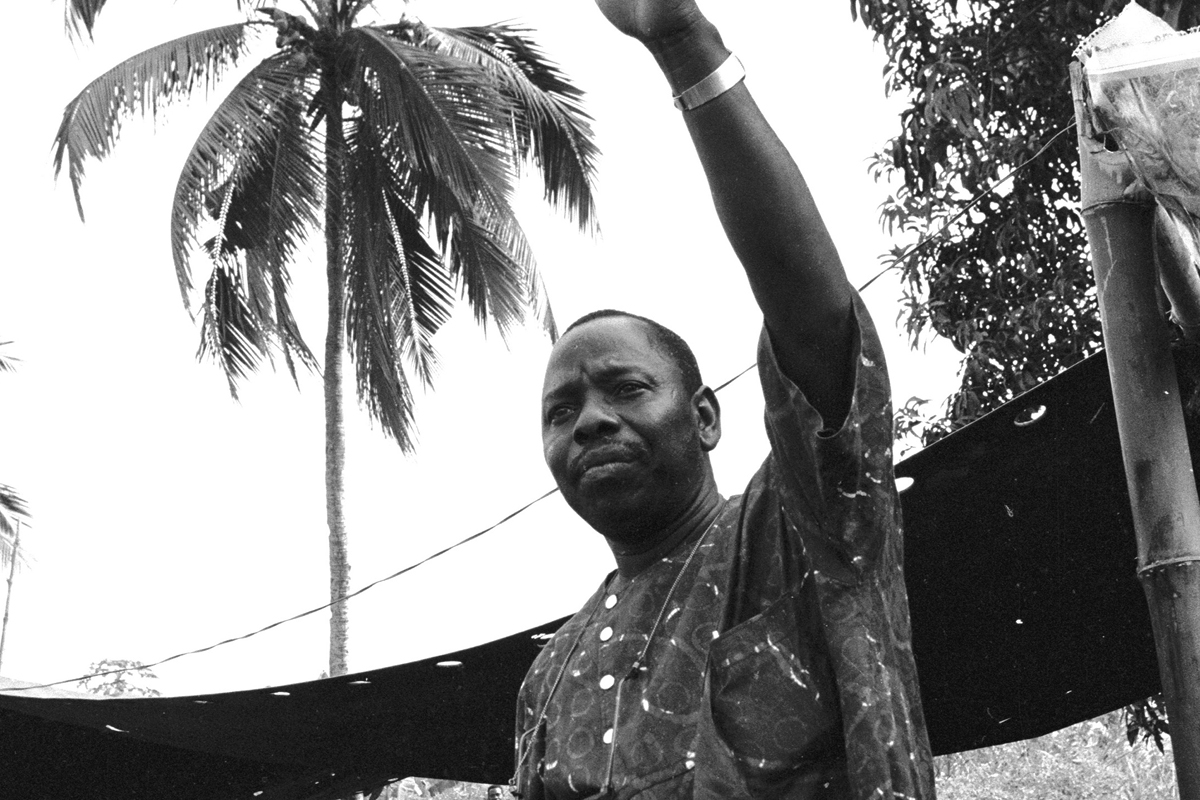

On November 10, 1995, the military government of Sani Abacha in Nigeria hanged Ken Saro-Wiwa, a Goldman Environmental Prize recipient, and eight other Ogoni activists who opposed Shell’s involvement in the area.

“The military dictatorship holds down oil-producing areas such as Ogoni by military decrees and the threat or actual use of physical violence so that Shell can wage its ecological war without hindrance… This cozy, if criminal, relationship was perceived to be rudely disrupted by the non-violent struggle of the Ogoni people under MOSOP. The allies decided to bloody the Ogoni in order to stop their example from spreading through the oil-rich Niger Delta.” – Ken Saro-Wiwa’s closing statement at the trial of the Ogoni 9

The men were held for months without charges, tortured while under detention, and sentenced to death by a “Special Tribunal” convened in violation of international law. They were executed for their peaceful efforts to defend the indigenous Ogoni people of Nigeria from human rights and environmental abuses caused by oil extraction activities of Shell Nigeria.

The evening before the trial in June 2009, Shell agreed to a settlement of all three cases and provided $15.5 million to compensate the plaintiffs, which included the establishment of a trust to benefit the Ogoni people.

“We will not move from our home village!”

In Cambodia, the Lower Sesan II dam poses a major threat to nearby communities. Almost 200 families, many of whom are indigenous Bunong, refused to move to a resettlement area to make way for the dam for fear they would lose their ancestral sites, cultural traditions, and livelihoods. They also chose to decline a compensation package from the Cambodian government.

“Our ancestral graves cannot be compensated with cash or moved from our village,” said a woman from Kbal Romeas. “Our culture, traditions, identity, and guardian spirits have strong connections to the land, which is our home. These strong connections enable us to use natural resources in the forest and river in sustainable ways. This has been recognized and respected as the right of indigenous people.”

In mid-July, the gates to the dam opened, filling the reservoir for operations testing. As a result, families who chose to remain in the Srekor and Kbal Romeas communities have endured dangerous floods. Unfortunately, flooding is only one significant impact from this dam. Villagers are also protesting the removal of a bridge that connects them to a town with access to schools, markets, and hospitals. There is no alternative route planned.

Although these villagers face an uncertain future, they are entitled to certain rights – and that will not change.

——-

The Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People is the most comprehensive international set of guidelines on the rights of indigenous peoples. It establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the “survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.” It is clear, Indigenous communities often find themselves as the targets of corporations that value profit over people. We remain committed to working alongside brave indigenous communities around the world in their pursuit of justice.

Perhaps we should take the time to read the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People more often and ask, are we really following through on what we set out to do a decade ago?

In solidarity.