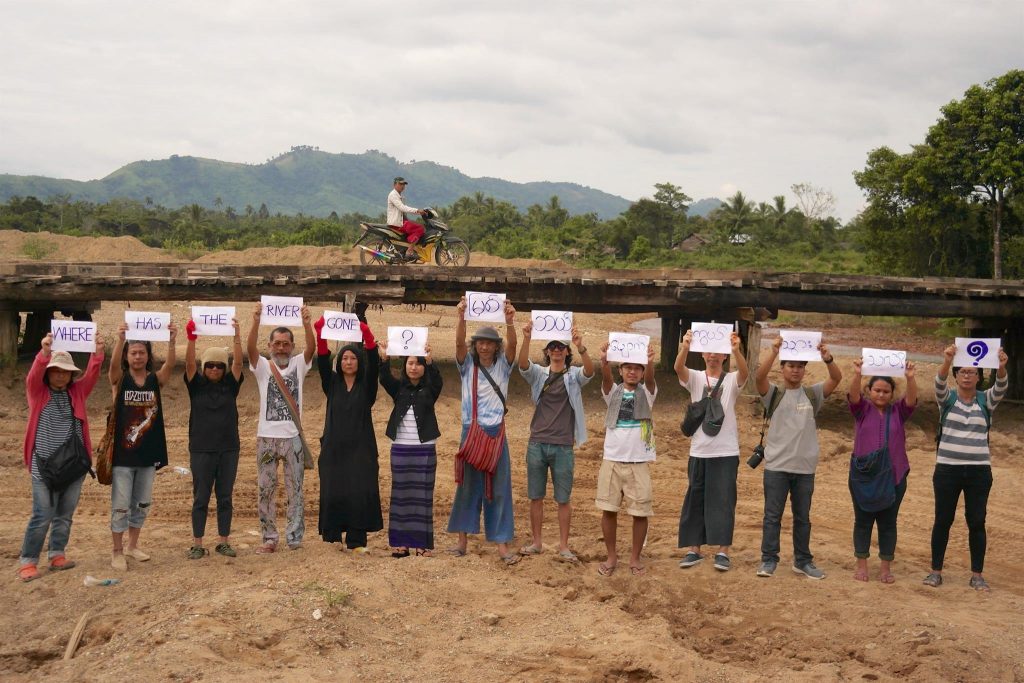

The Myaung Pyo River in Dawei, Myanmar once ran along the outskirts of the Heinda tin mine. Communities nearby relied on the river for drinking and irrigation water. But as the Heinda mine grew, mining waste and sediment smothered the river. Where the river once ran, today there is an expanse of sand and dust.

Supporters of Dawei communities pose in the dry riverbed of the Myaung Pyo River, asking “Where has the river gone?” (In Myanmar language (Burmese), “Myit bae pyauk twar thar hlae?”).

The Myaung Pyo River didn’t have to dry up – development could have taken another course. The mining corporation had a responsibility to monitor the river, but they didn’t. And when local communities spoke out about the deteriorating health of the river, as well as their own health problems, the corporation refused to listen.

The corporation and government could have made community voices central to decision-making, and asked them what was happening to the river. The same is true for the recent collapses of the Xe Nam Noy dam in southeastern Laos and the Swar Creek dam in central Myanmar. These disasters are preventable – if we ask communities to shape development to meet their needs and incorporate their local knowledge.

World Rivers Day: Celebrate What We Have

On World Rivers Day, we’re reminded what’s at stake across the world’s river basins. In the case of the lower Mekong river basin, 60 million people rely on the river for their livelihoods. Its ecosystems account for a quarter of the world’s freshwater fish catch. The only river basin that’s more biodiverse is the Amazon, home to 3,000 fish species.

But across the world, hydroelectric dams have already displaced as many as 80 million people, devastating river communities. There are now plans to construct 131 dams across the Mekong basin.

Let the Experts Plot the Course

The scope of this crisis is stunning, but the solution is clear: the only responsible path forward is to listen to the experts – the tens of millions of local people across these river basins who understand their environments and climates in a way no one else can.

Local residents catch fish in the O’Tabok River in Cambodia.

Local communities often already know what will happen if corporations and governments refuse to listen.

In Peru, the Chadín 2 hydropower dam is one of over 20 dams planned for the Marañón River. The reservoir for the Chadín 2 dam will displace over 1,000 people in the Cajamarca and Amazonas areas, flooding their land and threatening vital ecosystems. Together with communities who will be affected by the project, we filed a landmark lawsuit against the Peruvian government, calling for the project to be cancelled. The plaintiffs are waiting for the government to respond.

In Laos, local communities are refusing to consent to plans for the Pak Beng and Pak Lay dams on the Mekong. For the Pak Beng dam, communities in Thailand who would be affected have filed a lawsuit in Thai court that alleges public consultations for the dam were insufficient. For the Pak Lay dam, community-based groups say they will not participate in any public consultation processes until corporations and governments address unresolved concerns about other Mekong mainstream dams – the Pak Beng dam, the Xayaburi dam in Laos, and the Don Sahong dam in Cambodia.

Fisher people work along the Mekong River in Cambodia.

Local voices often struggle for their place at the decision-making table. But it doesn’t have to be that way. On World Rivers Day, we need to realize that any strategies to protect our rivers must begin with listening. We need to ensure local communities are central to decision-making. We need to ask them what will happen if we continue on the current path towards development, and then ask ourselves – and our governments and corporations – is this worth it?