On August 1, 2024, Peruvian plaintiffs who allege they were exposed to lead poisoning as children due to corporate decision-making by companies in Missouri and New York celebrated a win in their years-long lawsuits, consolidated as Reid v. Doe Run Resources, Corp.

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals issued an important ruling reaffirming that a case alleging wrongdoing in the United States under state tort law should be heard in United States courts, even if the harms resulting from said wrongdoing occurred abroad. In doing so, the court rejected the defendants’ arguments that the U.S. district court should decline its jurisdiction to hear the case on the grounds of international comity, a legal doctrine concerned with preserving foreign relations and foreign sovereignty. The Eighth Circuit’s decision sends the case back to the U.S. district court in Missouri to decide the merits of the parties’ summary judgment motions.

The Eighth Circuit’s ruling sets a helpful precedent for foreign plaintiffs seeking to hold U.S. companies accountable for harms felt in foreign countries in two key ways. First, the court declined to apply the international comity doctrine prospectively, i.e. without a pending or final foreign judgment, asserting that such an application must be limited to rare cases involving powerful diplomatic interests. Second, the court declined to dismiss the case on extraterritoriality grounds, holding that allegations of misconduct in the United States are appropriately subject to state tort law. Additionally, the court held that dismissal of the case was not required under the Trade Promotion Agreement between the United States and Peru, since the plain language of both the treaty and its implementing statute allowed the plaintiffs to bring a civil suit for the harms alleged.

EarthRights International filed an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief in the case in September 2023 on behalf of former U.S. diplomats and government officials, who argued that accountability in U.S. courts is a bedrock of U.S. foreign policy, including when American companies engage in domestic malfeasance that causes harm abroad.

The Environmental Damage and Resulting Health Harms in the La Oroya Village in Peru

The plaintiffs are 1,420 individuals from the remote Andean village of La Oroya in central Peru, where they lived as children. In 1997, several American companies based in Missouri and New York, including the Doe Run Resources Corporation and The Renco Group, Inc., purchased the La Oroya Metallurgical Complex through Peruvian subsidiary companies and began overseeing and directing the activities of the complex from the United States. The complex used smelters and refineries to process copper, lead, zinc, and other metals from 1922 until it ceased operations in June 2009.

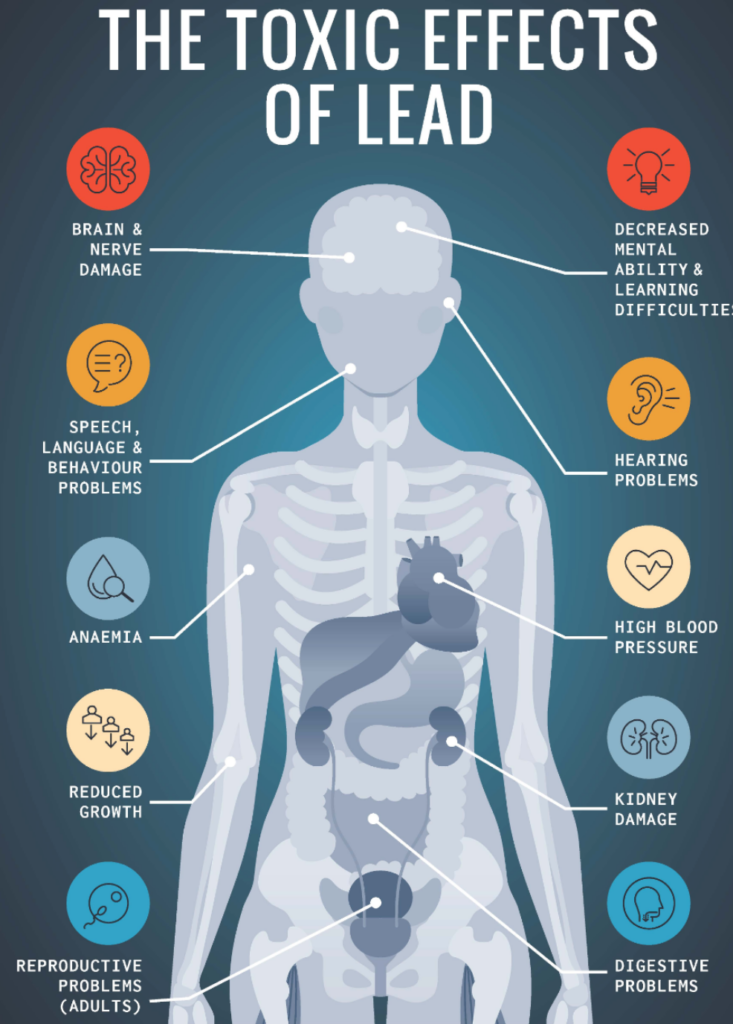

The plaintiffs allege that the U.S. companies directed the complex to emit excessive levels of toxic substances into the environment, including failing to sufficiently reduce lead emissions. These acts exposed the plaintiffs to lead and other toxic substances as children and caused them to suffer persistent and irreversible cognitive impairments and other medical harms. The first group of plaintiffs filed their suits in 2007.

La Oroya has been recognized as one of the world’s most polluted places, with estimates suggesting that 99% of children in the town had excessive levels of lead in their blood at the time the first lawsuits were filed. Excessive and dangerous pollution persists to this day in the village. In March of 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the government of Peru had violated the rights of La Oroya residents affected by decades of toxic contamination by failing to ensure environmental cleanup and ordered the government to engage in comprehensive remedial measures.

U.S. Courts Should Only Decline Cases Based on Prospective International Comity in Rare Instances Involving Powerful Diplomatic Interests, If at All

The Eighth Circuit rejected the defendant companies’ efforts to significantly expand the doctrine of international comity. International comity is an abstention doctrine where a U.S. court can decline to hear a case out of respect for another country’s laws or policies. The doctrine of international comity is generally applied retrospectively: U.S. courts have typically invoked the doctrine to decline to hear cases in the United States where a foreign court has already issued a judgment involving the issues at hand, or because a foreign proceeding is still occurring in parallel. Neither is true in this instance, however. Rather, defendants argued that the U.S. court was required to apply international comity prospectively and find that the case should more appropriately be heard in Peru in a future case to avoid running afoul of the interests of the United States and Peru.

The court explicitly declined to take a stance on whether such a prospective application is appropriate at all, reserving the right to reject any such prospective application in the future. Instead, it only stated that other courts have applied international comity prospectively in rare instances. The court found that if such a prospective application is ever appropriate, it must be reserved for “rare (indeed often calamitous) cases in which powerful diplomatic interests of the United States and foreign sovereigns aligned in supporting dismissal.” The court concluded that since neither the U.S. State Department nor the government of Peru had submitted declarations on their positions on the La Oroya case or asserted infringements on their sovereignty, despite 15 years of litigation and requests from the parties to do so, this was not such a rare case where prospective application of international comity may be warranted.

This precedent reaffirms that U.S. companies cannot have cases thrown out of U.S. courts on international comity grounds without a conflicting foreign proceeding, unless there is a clear showing that U.S. and foreign interests support the dismissal of the case.

Corporate Decision-Making and Directives in the United States are Subject to State Tort Law

The court also declined to extend the recent Supreme Court holding in Nestle v. Doe by rejecting the defendants’ argument that the case should be dismissed based on extraterritoriality concerns. Issues of extraterritoriality arise when U.S. courts are asked to apply U.S. law to conduct abroad without clear authority to do so. In Nestle, the Supreme Court found that plaintiffs seeking redress for forced labor on cocoa farms in West Africa had not sufficiently alleged domestic conduct in the United States, and were inappropriately seeking to apply a federal law, the Alien Tort Statute, to conduct that took place primarily abroad.

In the case involving La Oroya, conversely, the court held that the Peruvian plaintiffs were seeking to apply Missouri state tort law to conduct they allege took place in the United States. The Eighth Circuit upheld the district court’s finding that the Peruvian plaintiffs were not seeking an inappropriate extraterritorial application of the law after its detailed analysis of discovery materials that supported the allegations of corporate decision-making and directives in the United States.

The Eighth Circuit’s holding affirms the important hallmark of U.S. tort law that plaintiffs, whether domestic or foreign, can bring state tort causes of action against defendants where they commit tortious acts. This ruling sends an imperative reminder to American corporations that they cannot shirk legal accountability for causing harm abroad through their actions in the United States by inappropriately seeking dismissal under international comity.