In June, TC Energy, the company behind the Keystone XL pipeline, announced plans to pull the plug on its controversial project, handing a decisive victory to frontline communities that had opposed its construction. But as some environmentalists celebrated this victory, many were in Minnesota rising in solidarity with Indigenous communities facing a new threat–the Line 3 pipeline. Proposed in 2014 by the Canadian energy company Enbridge, which is already responsible for the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history, Line 3 would extend approximately 338 miles through Northern Minnesota, carrying a projected 760,000 barrels of tar sands oil each day across 227 lakes and rivers (including the Mississippi River), over 800 protected wetlands and ceded lands. The pipeline will snake through lands where local tribes have retained treaty rights for recognized activities.

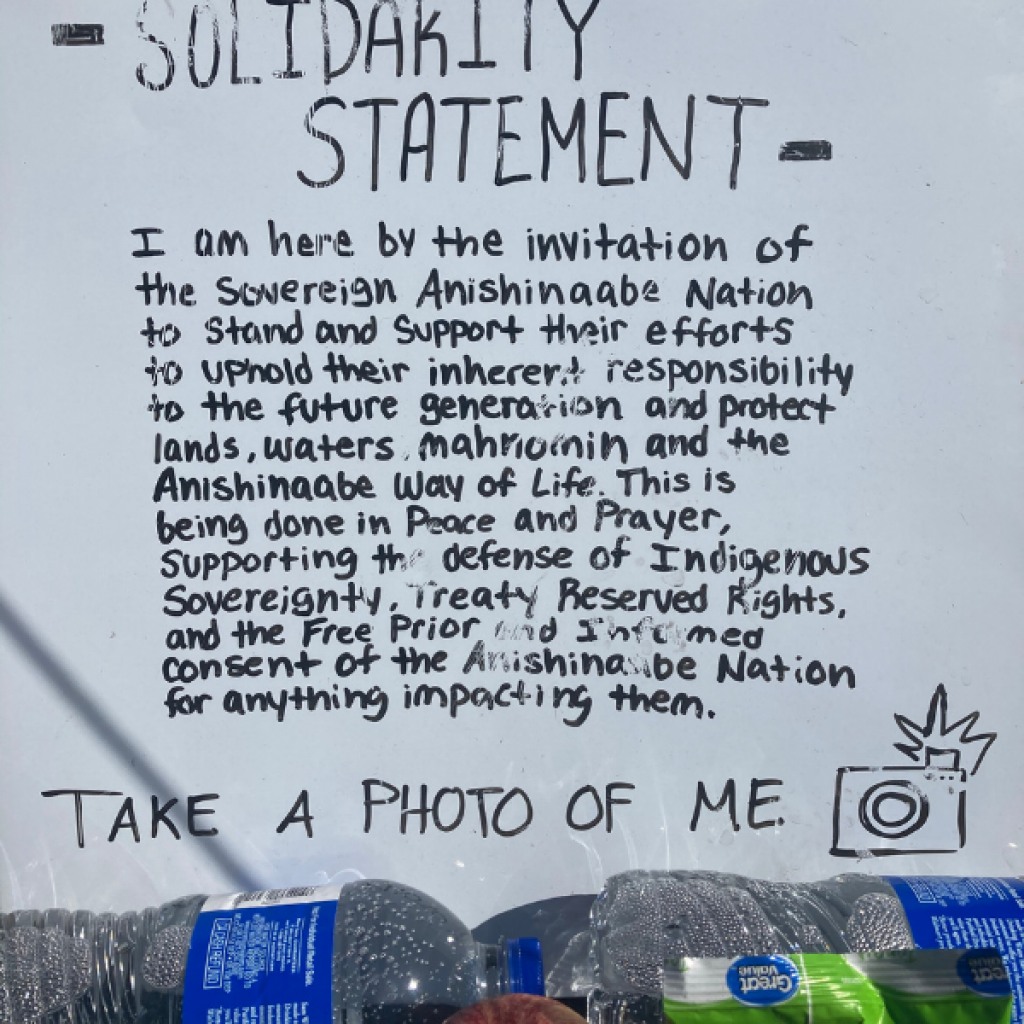

Indigenous communities living in its path vehemently oppose the expansion of Line 3; in February of 2017, water protectors set up resistance camps, intent on organizing and protesting in opposition to the project. Last month, my colleagues and I heeded the call from Indigenous leaders to come to Line 3 and join them in their resistance at the Treaty People Gathering. When we arrived, we found community and courage among the urgency and devastation that the pipeline posed.

Broken Treaties

Between 1842 and 1855, the U.S. government and the Ojibwe bands signed several treaties requiring the bands to cede land to the U.S. government, under the agreement that tribal members would still be guaranteed the rights to hunt, fish, gather plants, harvest and cultivate wild rice, and preserve sacred or culturally significant sites. This right is upheld by the U.S. Constitution and affirmed by the Supreme Court.

But Line 3’s proposed route would destroy wild rice beds, risk catastrophic spills, and directly contradict guarantees to usage rights that the treaties ensured.

“Treaties are the last big environmental protection tool available to all of us,” said Bob Shimek, an Indigenous elder, to the crowd of nearly 2,000 at the Treaty People Gathering, the largest non-violent direct action yet at Line 3.

Shimek asked us all to consider what good is a treaty right to fish if the fish aren’t safe to eat? What good is a treaty right to land, water, and air if it’s polluted with oil? What good is a treaty right to the rivers if Enbridge is allowed to pump billions of gallons of water out of it during a drought?

What good is a treaty right if only one side is upholding its end of the deal?

EarthRights to Line 3

I spent nine days on the frontlines at Line 3, living and learning from the community of water protectors in a resistance camp, led by Indigenous women and two-spirit people. As invited guests of Anishinaabe Nation, allies from across the country stood with them in defense of their land and water to set up camp Fire Light at the pipeline’s first planned crossing of the Mississippi. The space was spiritual and sacred; the Anishinaabe people held a water ceremony in the Mississippi headwaters and welcomed allies into the ceremony.

The space was also grounded in community, as we needed to sustain the camp on splintery wooden planks in the middle of rural Minnesota. To survive the 90-degree heat and lack of immediate resources, we relied heavily on each other and the Mississippi River, which cooled us, bathed us, and grounded our movement. Surrounded by protected wetlands, dragonflies darted in and around the camp. We later learned that dragonflies are thought of as spirit guides. There were so many.

When we walked out to the camp at the river crossing that first day, most of us did not have tents. There were no bathroom facilities. We didn’t have a centralized food tent or medic tent. And, it stormed the first night. As Nancy Beaulieu, an Indigenous leader at Camp Fire Light, said, “The first night is the hardest.” Within days the camp had bathroom facilities, a waste-management team, a designated medic area, a food system, a welcome team, and other camps at Line 3 sent more people and food donations. Born from community, the camp thrived. During the day, people sorted themselves into different jobs and relied on each other to stay healthy in the heat. At night, we were welcomed to take part in sacred ceremonies and camp meetings. The juxtaposition of this collective gift we built and the generations-bound curse that the pipeline poses at that same location was ever-present in our minds. The dread that this pipeline might ruin this place stuck in my throat for the entire nine days.

At the time of this writing, Enbridge is preparing to construct the pipeline across the Mississippi, at the same location that water protectors gathered and held space for nine days. When asked to leave by authorities, Indigenous leadership at the camp held off for as long as possible, and about 50 people were given citations. And now Enbridge prepares to drill. Each action like this one can only protect the environment from destructive construction for so long.

Harassment and Surveillance at Line 3

Since I left the frontlines of Line 3 in early June, the Enbridge-funded police force in Northern Minnesota have only escalated their response to the pipeline resistance. When water protectors non-violently occupied an active Enbridge work site to protest construction in June, 200 people were arrested and subjected to a low-flying helicopter, sonic weaponry (LRAD), and police violence. Water protectors report constant Enbridge and police surveillance and harassment; arrests happen almost daily now. And just this month, people staying at the Giniw Collective, a camp along the pipeline route, were barricaded in the camp by police, who refused to let them in or out of the camp’s driveway.

In response to the unlawful blockade, EarthRights joined Tara Houska, Winona LaDuke, and the Center for Protest Law and Litigation to file an emergency lawsuit, asking for a restraining order against Hubbard County, Sheriff Cory Aukes, and the local land commissioner in northern Minnesota. Last week, this restraining order was granted.

There are daily examples of harassment that don’t make major news articles. Every water protector I met had a story about intimidation or surveillance. From unnecessary traffic stops to Enbridge drones and helicopters flying over resistance camps, these stories add up to a narrative showing the coordinated effort from corporations and the state to quell pipeline-opposition movements. It shows disrespect for the treaties, which we all signed and benefit from. It highlights the link between police and extractive projects. For Line 3, Enbridge has set up an escrow account to fund police activity at the pipeline. So far, the Canadian corporation has paid over $1 million to local police in northern Minnesota through the fund.

These stories are part of a global pattern of communities and defenders worldwide resisting fossil fuels and facing intimidation, threats, and harassment from corporate-funded security forces. An EarthRights report exposed that police officers in Peru contract with companies to take on security work at private extractive projects, compromising their ability to protect the rights of people opposing extractive projects.

Privatizing police to protect private property undermines the state’s ability to serve the public and shields fossil fuels and other extractive industries from protest and opposition. Using the power of the state against the people at the behest of a corporation is dangerous and wrong.

An Escalating Climate Crisis

In the last month, a gas pipeline exploded in the Gulf of Mexico and the ocean caught fire. Germany’s streets flooded and infrastructure melted in Oregon. Every year is deemed the worst year on record for extreme weather events like flooding, wildfires, heatwaves and hurricanes. Every year it gets worse.

We’re watching the world suffer under the weight of a climate crisis amplified by fossil fuels, and here we are, building a new tar sands pipeline, doubling down on our current addiction to fossil fuels. What feels most unfair about it all is that we don’t have the time. We’re spending the resources we have fighting corporations and pipelines. Rather than uniting to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis, we’re fighting so that a multinational doesn’t destroy the clean air of thousands, the drinking water of millions, and the livability of a world for generations to come. And that’s just at Line 3. This fight is replicated around the world on the frontlines of climate justice.

Governments must act. We can’t rely on the same industry that hid the climate crisis for 50 years to regulate itself away from fossil fuels. The Biden administration must heed the calls from the Indigenous communities and cancel Line 3.

At best, the Biden Administration has ignored Indigenous communities, at worst the administration has disrespected them and broken treaty agreements. And why? As the climate crisis escalates we should be taking the lead from Indigenous people. Globally, Indigenous peoples represent about 5 percent of the world population, yet they steward 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. Humans know how to steward the land, and we must be given the chance to do so.

In June, President Biden affirmed his support for Line 3, despite the environmental dangers it poses and the continued calls from Indigenous communities to cancel Enbridge’s permits. Globally, the U.S. bears the most responsibility for the climate crisis, as it tops the list of countries with the highest cumulative CO2 emissions since the 1970s. Sanctioning a pipeline with the carbon offsets equivalent to 50 new coal-powered plants is not just negligent, it is derelict of our duty to the global community.

Fighting for Justice

“It’s more than a pipeline, it’s about justice, treaty justice, racial justice, climate justice,” said Dawn Goodwin, Fire Light camp leader, and White Earth Indigenous water protector.

The fight to stop Line 3 is the fight for treaty rights, for racial justice, and Indigenous sovereignty. An art piece representing the cross streets of George Floyd plaza gifted from activists in Minneapolis was displayed at camp, reminding all of us that the fight against injustice is deeply interconnected.

When we stepped into the Mississippi River that first day, and reveled in our collective power that got us there, I thought about something that was said earlier in the day:

“Water doesn’t separate the continents from each other, it binds us all together.”

Water protectors are asking for folks to join them at Line 3. Consider making the trip. If you’d like to support from afar, please donate to support the resistance camps.

Follow EarthRights case updates on social media to hear more about our Line 3 case.