A generation after being forcefully displaced by the Bhumibol Dam in Thailand, an indigenous community faces the prospect of a second displacement.

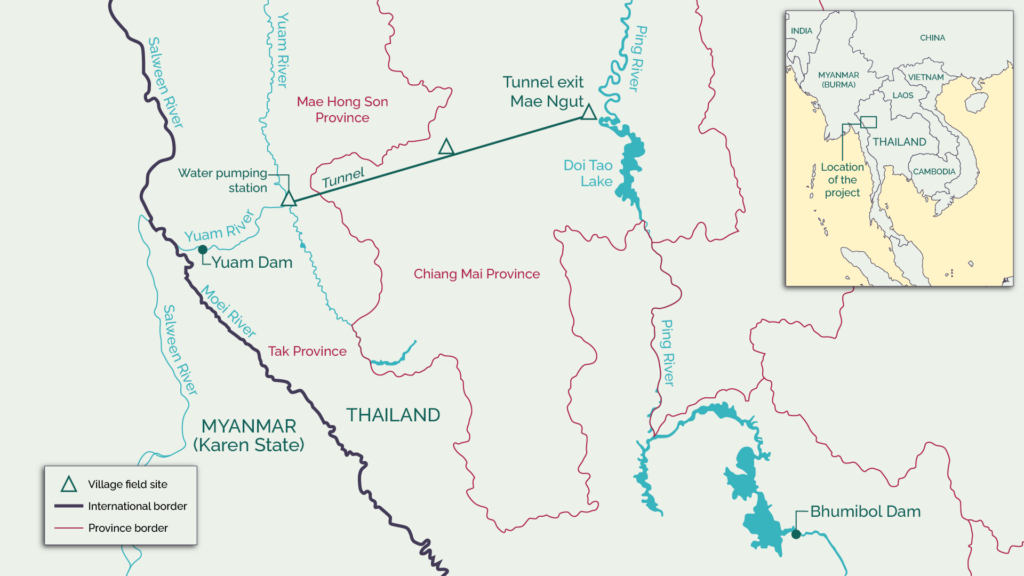

In the 1960s, the Karen indigenous villagers of Mae Ngut, located in the lush landscapes of Chiang Mai Province, were forced to leave their ancestral homes after being flooded out by the Bhumibol Dam. The villagers relocated to an elevated location where they were safe from the dam’s water overflows and could continue living in harmony with nature. Unfortunately, the government is now planning to construct a new project to divert water from the Yuam River to the Bhumibol Dam, which will pass through Mae Ngut. If this project proceeds, it will pose a serious threat to the village’s ecosystems, land, and livelihoods.

The Bhumibol Dam legacy

The construction of the Bhumibol Dam on the Ping River in the 1960s marked the beginning of a difficult journey for Mae Ngut’s survival. The village’s ancestral lands were submerged in water due to the damming of the river, which forced the inhabitants to leave their homes and means of livelihood. Several decades later, the scars of this forced relocation still linger.

Yupha, a resident of Mae Ngut, explained, “In the past, Mae Ngut’s original houses were not in here but down there. The water level went up and flooded our place, so we were forced to move up.”

The Bhumibol Dam is located in Tak Province, about 100 kilometers away from Mae Ngut. Its purpose is to provide additional water for irrigation and hydroelectric power for Thailand. However, several decades ago, the dam’s water overflowed and caused floods in Mae Ngut, which devastated the once-fertile fields where Yupha’s family and others grew rice. Many villagers had to abandon rice farming because their fields turned sandy and were no longer arable. Instead, they shifted to planting longan, which has now become Mae Ngut’s primary source of income.

Yupha was still a child when she experienced the floods. She feels that the government ignored the rights of the Karen indigenous villagers in Mae Ngut in the past for the sake of Thailand’s economic development. Additionally, she believes that her community did not receive adequate support for relocation.

Our elders did whatever they were asked to do and signed documents using their fingerprints. But when the time came for us to move to a new place because of the floods, no one was there to help. The government agencies did not show up.

Yupha, a resident of Mae Ngut

The Yuam River’s water diversion project

Today, several decades after the floods occurred, the villagers of Mae Ngut are confronted with a new threat in the form of a project to divert water from the Yuam River to the Bhumibol Dam. This recent project could lead to a second forced displacement for the Mae Ngut villagers.

The project would involve the construction of a 60-kilometer tunnel to divert some water from the Yuam River in Mae Hong Son Province to the Bhumibol Dam. However, Mae Ngut is situated right at the tunnel’s exit and next to the creek where the water from Yuam River will be pumped out. Villagers are concerned that the project will have a permanent impact on their environment and livelihoods.

Sakchai, a longan farmer, said: “If water from the water diversion project comes in here, Mae Ngut will be flooded. My longan farm will be completely damaged. In fact, all farmers will be affected as the farmlands are close to one another.”

Lack of transparency and participation

In 2021, the government approved an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report to justify the construction of the water diversion project, valued at 70 billion baht ($2 billion). According to the report, the project will bring several benefits to Thailand, such as 300 million cubic meters of water, 460 million kilowatt-hours of electricity, and revenue of 620,000 baht ($17,300) from fisheries annually. Additionally, it will create 1.6 million rai (256,000 hectares) of arable land during the dry season.

Although the water diversion project has promised benefits for the wider population, the villagers of Mae Ngut have expressed their concerns about it. They claim that the decision-making process lacks transparency and genuine community participation. The villagers are also skeptical due to the inaccuracies and lack of reflection of community sentiments in the EIA report, which was meant to assess the project’s potential effects.

A particularly troublesome part of the EIA report, which has stirred up resentment among communities, claims that the entire project will only impact about 30 households. However, in Mae Ngut alone, there are almost 190 households, according to the latest population count. Many of these households could lose their sources of food, property or income, or face health risks from pollution resulting from the project.

Additionally, villagers recall instances of disinformation from project contractors, highlighting the intentional cover-up of the project’s actual impacts.

They came here and shared flawed information. They told us that the project would only affect three people. I don’t believe that because I know everyone in the village will be affected.

Sakchai, a longan farmer

Cultural implications

The Yuam River’s water diversion project poses a threat not just to the land and livelihoods of the indigenous Karen community but also to their identity and culture. For Wanchai, who is the leader in the village, the project’s lack of consideration for the sacred forests is a violation of their right to uphold their indigenous beliefs and traditions. It also perpetuates inequality in Thai society.

An estimated 3,500 rai (560 hectares) of forests will be cleared for the project. The tunnel will traverse through five forest reserves and one national park located in three provinces – Tak, Mae Hong Son, and Chiang Mai. Additionally, the materials used for construction and the soil extracted from drilling the tunnel will be disposed of in six different locations, including Mae Ngut.

In our indigenous culture, we have sacred forests, and we take care of them. If the project comes here, our sacred forest will disappear.

Wanchai, village leader of Mae Ngut

A call for justice

The villagers of Mae Ngut are facing the threat of displacement once again. However, they refuse to be silenced and are using the lessons from the impact of the Bhumibol Dam to inform their actions. The community’s painful memories of past injustices have become a rallying cry to reject the proposed project.

“We stand up and fight. We won’t accept the project. We are no longer like before when we just followed what government agencies said,” said Wanchai, the village leader of Mae Ngut.

In 2023, Wanchai and more than 60 other individuals from indigenous communities that could be affected by the water diversion project filed a lawsuit against five government agencies responsible for progressing the project. The lawsuit questions the legality of the project and its EIA report, which Thailand’s National Environment Board approved.

The struggle of the Mae Ngut community against the Bhumibol Dam and the planned water diversion project is becoming more urgent each day. As the world watches, let their voices resonate far and wide, reminding us of the consequences of unchecked development that attempts to sacrifice the well-being of indigenous communities without their consent.

“What else do we have to sacrifice? We have suffered once before. The quality of life remains the same and didn’t get any better,” Wanchai added.